UK NANDTB – policy on remote NDT

13/06/2022

Remote non-destructive testing (RNDT), where personnel at more than one location collaborate on an NDT task, is nothing new, but perhaps it has not been treated as a separate concept until recently. Since the 1970s, a Level 1 may take a radiographic exposure, process the film, check the image quality, then send the radiograph to a Level 2, who interprets it and sentences the part.

Recent technological advances, such as in digital file transfer and live streaming, have created the potential for working synchronously (‘live’) and possibilities that were not considered when EN 4179 was written are now becoming quite widespread and established in the remote visual inspection (RVI) and medical fields.

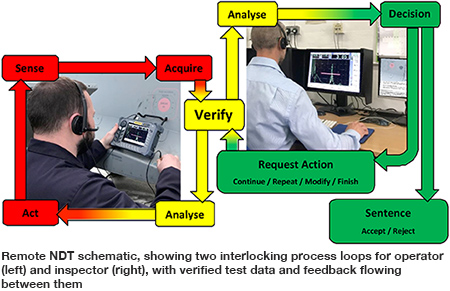

During COVID restrictions, remote solutions were pursued in NDT for everything from audits to task-specific training (with varying degrees of success, as anyone who has felt vaguely seasick while a camera is walked round and pointed at various items over a video call can attest). This has led to the question: could you have NDT data collected and beamed back by a ‘deployed’ operator, for live interpretation and sentencing by experts ‘at base’? The advantages of this are clear, but whether it would be a good idea or not from a technical perspective is another matter: it introduces significant human-factor complexities, with multiple interacting feedback loops.

The UK National Aerospace NDT Board (NANDTB) recognised a need to create a framework and consistent terminology to assess remote NDT, balancing the control and assurance of NDT with enabling innovation. A task group, including end-user, original equipment manufacturer (OEM), regulatory and service-provider perspectives, has authored NANDTB/29 (remote NDT), which has recently been published.

This policy has been written at a principles level to be independent of any specific technology or NDT method and incorporates requirements, recommendations, guidance and example case studies. The key concept is that of ‘verification’: establishing which person/system is responsible for assuring the integrity of test data, providing corrective feedback to resolve shortcomings with the test conditions or test results and certifying the above. Examples of verification models and a flowchart to help choose the appropriate verification model are provided.

The policy sets six minimum requirements. Additional requirements may be specified by the National Aviation Authority (NAA), Responsible Level 3 or client:

- The RNDT policy must be defined in the organisation’s exposition or written practice, for approval by relevant NAA(s).

- Operators and inspectors must be certificated appropriately in accordance with EN 4179 and trained in RNDT (remote supervision of uncertified personnel collecting NDT data is not allowed).

- A task-specific risk assessment to identify additional controls must be carried out.

- A standalone RNDT work instruction, which clearly defines the certification levels, responsibilities and procedural steps for each person, must be issued.

- NAA approval must be obtained before first use of each synchronous RNDT application (unless all verification is carried out by the inspector and the RNDT inspection is in the approved OEM data).

- Enduring records of the inspection must be maintained to allow future review and audit. These need to cover test conditions, test results and procedural compliance and will likely need to be more comprehensive than the non-RNDT equivalent.

The full policy can be found at www.bindt.org/NANDTB/UK-NANDTB-Documents and any questions or clarifications should be directed to nandtb@bindt.org