Personnel Certification in NDT and CM: BINDT’s point of view

18/06/2015

One of BINDT’s key propositions is personnel certification, which it provides through the PCN Scheme, covering programmes that include non-destructive testing (NDT) and condition monitoring (CM) across a number of industry and product sectors. In other words, amongst other things, BINDT is a Personnel Certification Body (PCB).PCN is a central (or third-party) certification scheme, as opposed to an employer-based (or second-party) certification scheme, which means that a certificate issued under the scheme indicates conformance to an international standard and competence to undertake certain prescribed, generic NDT or CM tasks.

More information about the PCN Scheme, BINDT’s accreditation and the various programmes and standards covered can be found on the BINDT website[1].

Ultimately, the aim of personnel certification is to provide assurances to those who rely on the tests being undertaken (for example end-users, regulators, insurers, etc) that they have been carried-out competently. And that is what PCBs and diligent employers set out to do. However, there are some misunderstandings that keep cropping-up around personnel certification, which can lead to unrealisable expectations being set which, in turn, can lead to damage being done to the respective certification scheme’s reputation and, indeed, damage being done to the reputation of the whole NDT/CM profession.

The aim of this paper is to address three apparently common misunderstandings:

- About the role of personnel certification in assuring the reliability of NDT, CM, etc.

- About the role of central certification in personnel certification.

- About the roles of multilateral recognition agreements (MRAs) and harmonisation.

Cameron Sinclair, BINDT CEO, presents BINDT’s point of view on these matters…

Organisations: definitions

In this paper, there is reference to three different organisations:

- ‘End-users’ who, in the context of this paper, have ultimate responsibility to ensure that the items subject to NDT or CM are safe and reliable, since they have duties of care to their employees, customers and members of the public.

- ‘Employers’ who employ the people who will undertake the NDT or CM work. In the context of ‘employer-based certification schemes’, employers operate these schemes.

- PCBs who operate central certification schemes.

PCBs must always operate their central certification schemes demonstrably independently, meaning that end-users and employers must not be able to exert undue influence[2] over a certification decision.

End-users and employers could be the same organisation: for example an end-user might also perform (and, crucially, control) the NDT or CM utilising:

- Their own staff.

- A pool of sole-trader contractors operating in accordance with the end-user’s business management systems.

- A pool of subcontractors sourced via an agency contractor and in accordance with the end-user’s business management systems.

Where an end-user contracts-out the provision (and control) of the NDT or CM to a contractor, then that contractor is the employer, for the purposes of this paper. Under such an arrangement, the contractor shares responsibility with the respective end-user for ensuring that the personnel provided are competent.

Role of personnel certification

The reliability of a NDT or CM system can be thought of as a function of the reliability of three elements of the system: the equipment, the procedure and the personnel. All three of these elements need to be considered when specifying NDT or CM. So, the role of personnel certification is to help maximise the reliability of the personnel element of the NDT or CM system.

Bear in mind that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. In other words, the failure of NDT or CM to detect or characterise a defect or fault may not be due to a lack of competence of the personnel undertaking the work (though that might be the root cause). As the UK Health and Safety Executive’s PANI[3] research programme showed, it may be due to one or more of a number of different factors.

One such factor is a mismatch between the types of defect or fault arising and the NDT or CM system deployed. The whole NDT or CM system needs to be qualified or validated by the end-user and, although personnel certification has an important role in the qualification process, it is just one part of the qualification process.

Another set of factors adversely affecting the reliability of NDT or CM are ‘human factors’. Personnel certification (whether central or employer-based) cannot be used as an accurate indicator as to how an individual will behave when at the workplace.

Role of central certification

Central certification, when provided by PCBs that are accredited by a national accreditation service (such as UKAS, in the UK), has the benefit of independence and impartiality, and a certificate issued by such a body provides assurance that the holder conforms to an international standard.

For example, a certificate covering an NDT method may demonstrate conformance with ISO 9712[4] and a certificate covering a CM method may demonstrate conformance with ISO 18436[5].

However, conformance with such standards does not necessarily demonstrate competence to undertake a given NDT or CM task.

The following three simplified examples are given in order to make this point:

- The task is to undertake magnetic particle inspection (MPI) of a carbon-steel component subject to fatigue cracking on the available surface. A central certification certificate covering MPI will be both suitable and very nearly sufficient.

- The task is to undertake ultrasonic testing (UT) of a welded node junction joining a number of tubular elements as part of an in-service inspection programme. A central certification certificate covering UT of welds will be suitable, as it demonstrates a suitable level of proficiency in the method, but it will not be sufficient for this particular task (unless, of course, the certificate specifically covers this task).

- The task is to undertake a non-destructive test of an item using a novel and specialised technique that is not covered in ISO 9712. A central certification certificate will be neither suitable nor sufficient, though a central certification certificate in a similar method/technique might add some value in demonstrating a closely-related proficiency.

In order to ensure that the certification is definitely both suitable and sufficient in all three of the examples above, the certification would ideally comprise both central certification and employer certification. The three examples above would require different degrees of employer certification: example 1 requiring the minimum and example 3 requiring the maximum.

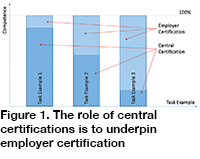

Figure 1 also serves to illustrate this point.

This is what BINDT advocates: that, where practicable, personnel certification for NDT and CM, etc, shall consist of employer-based certification, to demonstrate competence to undertake specific tasks, underpinned by central certification, and to demonstrate conformity to an international standard, independence and impartiality.

Therefore, the role of central certification is to underpin employer certification.

As one of the relevant central certification standards, ISO 9712 clearly states: the employer (see Organisations: definitions above) ‘shall be responsible [amongst other things] for all that concerns the authorisation to operate, for example providing job-specific training’ and ‘issuing the written authorisation to operate’ and, furthermore, that central certification ‘does not represent an authorisation to operate since this remains the responsibility of the employer’.

Multilateral recognition and harmonisation

Multilateral recognition does not necessarily mean equivalence.

A group of central certification schemes that are in an agreement, such as the ICNDT MRA[6], all demonstrably meet the applicable standards, or as the ICNDT puts it: ‘These Personnel Certification Bodies may therefore announce that holders of their certificates issued under these arrangements are certificated by a PCB, which is registered by the ICNDT as meeting the requirements of the applicable standards (including ISO 9712 and ISO 17024), and technical documents referenced in the schedule of conformity (scope) issued by the accreditor and/or the ICNDT.’

However, there may be some significant differences between the schemes where some schemes deviate (in a positive way – for example exceed specified minimum requirements) from the applicable standards, as shown in the ‘comparison of PCB’s schemes with ISO 9712’ spreadsheet published by the ICNDT[7]. For example, the PCN Scheme breaks down into industry and product sectors and, as the above referenced ICNDT document states: ‘The route to comprehensive Level 2 certification in UT (welds, wrought products and castings) in accordance with PCN GEN requires undertaking examinations three times over and, in effect, taking three specific papers.’

In future, some schemes may deviate significantly from the international standard ISO 9712, as allowed for by ISO Guide 21[8], but it is understood that this is being strongly discouraged by the ICNDT.

It should be noted that, in the UK, ISO 9712 is referenced as BS EN ISO 9712 and, at the European Union (EU) level it is referenced as EN ISO 9712. For countries in the EU, no deviation from EN ISO 9712 is permitted. In countries where deviation is allowed, the standard must not be referenced as ISO 9712 as ‘for modified adoptions, only a regional or national reference number is permitted.’

Therefore, the role of MRAs is to provide assurance to those who specify or purchase NDT or CM that the registered central certification schemes all meet a minimum (specified) applicable standard.

The role of harmonisation, however, is to demonstrate equivalence, so a group of harmonised schemes are as robust as each other, and holders of the respective scheme’s certificates should be equally proficient at a given generic task.

So, if a specification for NDT or CM stipulates something along the lines of ‘personnel must hold relevant XYZ certification[9] or equivalent’, the reader cannot simply refer to an MRA as indicating ‘equivalence’ and must instead either: (a) seek to get the specification changed (to read something along the lines of ‘personnel must hold relevant certification issued by a personnel certification body that is registered under the ICNDT MRA’); or (b) do research in order to identify those schemes that are equivalent in robustness to the XYZ scheme by reading various sources of information, such as the ICNDT ‘comparison of PCB’s schemes’ and the respective schemes’ documentation packages[10].

Concluding remarks

This paper gives BINDT’s view on three important aspects of personnel certification where BINDT believes there are some misunderstandings, particularly amongst those organisations that are end-users of NDT and CM.

Personnel certification has an important role in qualifying NDT or CM systems, though such certification cannot be used as an accurate predictor of the holders’ behaviour at work.

There are many factors that can lead to failures in NDT or CM to detect or characterise defects or faults. One reason for such failures is a mismatch between the NDT or CM system deployed and the types of defect or fault arising.

The use of suitably-certificated personnel, especially Level 3s, will help to minimise the likelihood of such a mismatch: in other words, suitably-certificated personnel should be able to ensure that all parties’ expectations are realistic. Indeed, in the aerospace industry, all NDT must be carried-out under the control of a Level 3 person (either an employee of, or contractor to, the organisation undertaking the NDT work). In BINDT’s view, all NDT that is performed in order to improve/assure safety, regardless of the industry sector, type of component, etc, should mandatorily be undertaken ‘under the control’ of a Level 3 as per the aerospace industry’s practice. It is accepted that it is often impracticable for a Level 3 person to be present on the site where and when the NDT or CM is being undertaken, but it remains BINDT’s view that a Level 3 person should have ‘control’ and take responsibility for ensuring that the NDT or CM system deployed is both suitable and sufficient.

As recommended in the ICNDT Guide on Certification of NDT Personnel[11], the role of central certification is to underpin employer-based certification and employer-based certification should feature in the qualification of all NDT or CM systems. The amount of additional experience, training and examination that an employer must provide, over and above that gained in order to attain central certification, depends on the specificity of the NDT or CM application, since central certification is, by implication, relatively generic.

The employer is responsible for ensuring that a NDT or CM practitioner has suitable and sufficient industrial NDT or CM experience in order to be authorised to carry out a particular job of work. The relevant international central certification standards make this very clear. End-users of NDT and CM should recognise the limitations that all central certification schemes have in terms of experience:

- Employers attest that the requisite experience has been gained by a candidate practitioner: it is impracticable for PCBs to verify this beyond relatively basic checks.

- The experience required will be relevant only to the certification issued.

- As discussed above, the central certification issued may not, in isolation, be both suitable and sufficient for the NDT or CM task that the end-user requires to be undertaken.

Using the same assessment processes that BINDT uses to accredit NDT and CM training, BINDT can provide independent, impartial accreditation of employer-based personnel certification schemes. BINDT can assess the respective schemes against the technical standards set-out in ISO 9712 or ISO 18436 (levels of certification, duration and quality of training, scope and toughness of examinations, etc) and would accredit those schemes that meet these technical standards.

If you would like to comment, please email the Editor (david.gilbert@bindt.org) by 31 July 2015.

| 1 | http://www.bindt.org/Certification/ |

| 2 | End-users and employers can exert influence through consultation and/or governance committee participation, but they must not exert undue influence over certification decisions. |

| 3 | http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/rr617.htm |

| 4 | ISO 9712:2012 Non-destructive testing – Qualification and certification of NDT personnel. |

| 5 | For example, part 2: ISO 18436-2:2014 Condition monitoring and diagnostics of machines – Requirements for qualification and assessment of personnel – Part 2: Vibration condition monitoring and diagnostics. |

| 6 | http://www.icndt.org/Documents/Document-Store?EntryId=12453 |

| 7 | http://www.icndt.org/Documents/Document-Store?EntryId=5411 |

| 8 | ISO/IEC Guide 21-1: 2005, Regional or National Adoption of International Standards and other International Deliverables – Part 1: Adoption of International Standards. |

| 9 | Where XYZ is some central certification scheme. |

| 10 | For example, see http://www.bindt.org/Certification/pcn-exam-requirements-and-document-download/ for the documentation covering the PCN scheme. |

| 11 | ICNDT Guide and Recommendations on Qualification and Certification of NDT Personnel, see http://www.icndt.org/Documents/ICNDT-Guide |